Geneva Bible - A Cornerstone of History

The Geneva Bible, first printed in 1560, shaped faith and culture for generations. Discover the first study Bible, which found its way into homes across England and eventually aboard the Mayflower to America.

Geneva Bible Popularity

The publication of the 1560 Geneva Bible marked a turning point in English Bible translation as well as the Protestant Reformation in England. Although five English Bible versions were available by this time, this book was produced and sold at a price that promoted private ownership. The marginal notes helped the reader grasp the meaning of the text, making it the first study Bible. When it was first printed in London in 1576, the ‘Breeches Bible’ instantly became the preferred Bible of the English people. Over 360,000 copies were printed in 180 editions for a country of around four million people: unquestionably, it was the most popular Bible for over a century. It was the first Bible brought to America carried by the Pilgrims on the Mayflower. It found its way into the works of both Shakespeare and Bunyan. Eventually its printing and importation were banned throughout England to promote the King’s official Authorized Version of 1611.

Editions of first generation English Bibles

1557 Geneva New Testament

Eighteen years after the impressive folio Great Bible of 1539, called ‘Great’ due to its impressive size, a small octavo was published in Geneva and translated by William Whittingham. This 1557 New Testament presented a stark contrast in size and a great leap forward in Bible translation.

Under King Edward, who saw himself as modern-day King Josiah, Bible printing and distribution flourished, but the coronation of Queen Mary on July 19, 1553 marked an about-face in the relationship between Bible publication and the nation of England. Queen Mary was a devout Catholic and actively sought to revert England back in line with Rome. Numerous Protestants departed to seek safety on the continent. Restrictions on Protestants who stayed behind began within a short time of Mary’s ascension. John Rogers, credited for his work on the Matthew’s Bible, was the first to be burned at the stake. Even though her reign lasted only five years, over three hundred protestants were burned alive during that time, earning her the nickname of Bloody Mary.

Mary Tudor (1516 - 1558)

John Calvin (1509 - 1564)

Many of the English reformers who fled during Mary’s reign settled in John Calvin’s Geneva, Switzerland. By November 1555 there were enough English exiles to establish their own place of worship, and they did so with Calvin’s help. William Whittingham was one of those congregants and a leading scholar. The 1557 Geneva New Testament was the work of Whittingham alone. His work was not approved or licensed by the royal crown, but translated illegally for the benefit of the English citizens. He translated the text from the original Greek, often consulting Tyndale’s translation and Beza’s recently published Latin New Testament. This ground-breaking book boasted wide margins and clear Roman font. Verses were numbered, and each new verse began on a new line. Study notes were provided in the margins. These changes made the New Testament much more approachable for the reader.

1560 First Edition Geneva Bible

After completing the New Testament, Whittingham spearheaded work on the Old Testament. He enlisted the help of Miles Coverdale, Anthony Gilbey, Christopher Goodman, Thomas Sampson, and William Cole. They worked directly from the Hebrew text producing the first Old Testament that did not depend on the Vulgate. For the first time, the Biblical text was divided into chapters with verses, packed with notes and commentary, and filled with helpful cross-references. The Geneva Bible stood apart as essentially the first ever Study Bible and became the most popular Bible of the 16th century. It revolutionized the study of Scripture through its size, font, illustrations, and notes. Prior Bible versions were issued as cumbersome folios, printed in a beautiful but hard-to-read Gothic type, and frequently chained to the pulpit. This Geneva Bible was a personal size quarto in a Roman font, intended to be read and studied from home.

William Whittingham (1524 - 1579)

Helpful Illustrations and Maps

Candlestick and Showbread

Two woodcut illustrations from a Geneva Bible

The 1560 Geneva Bible was the first of its kind in producing a complete study guide to the text, intended to educate and illuminate at every point. Previous translations including Tyndale, Coverdale, and the Great Bible contained narrative woodcuts that depict David eyeing Bathsheba or David conquering Goliath. But here the maps orientate the reader to the geographical locations of places in the text. The set of woodcuts are of priestly garments and the furniture in the tabernacle, bringing the articles and fixtures to life. The point was to enlighten the reader, to supplement the notes, and bring the student of the Scripture into a clearer understanding of the meaning of the text. The 1560 first edition contained five maps, 26 in-text illustrations, and two title page woodcuts.

Garden of Eden

A map showing the area around Mesopotamia

The Bible with Marginal Notes

The Geneva notes that filled the margins were added to help the reader understand and interpret the Scriptures. The notes were so popular that they were included in eight editions of King James Bibles between 1642 and 1715.

Once the 1611 King James Bible began to compete with the Geneva Bible, the distinction between the two Bibles was not focused on the difference in the text, but rather the presence of the beloved notes. The King James version was referred to as the “Bible without notes” and the Geneva Bible was “the Bible with notes.” The Geneva Bible was sometimes referred to as the Breeches Bible. This reference was based on the translation in Genesis 3:7 where Adam and Eve realized their nakedness and sewed themselves “Breeches” (KJV has “aprons”).

There is a tendency among historians to claim that the Geneva notes were so Calvinistic or anti-papal that it became necessary to release another translation without notes to rectify the situation. This is not true. While there are a handful of comments against the pope and a few that promote Calvinism, they are hardly the focal point. The notes, particularly the 1560 Geneva notes, are best depicted as a running commentary on the whole Bible; occasionally offering alternate renderings and providing cross-references, but mostly explicating the text.

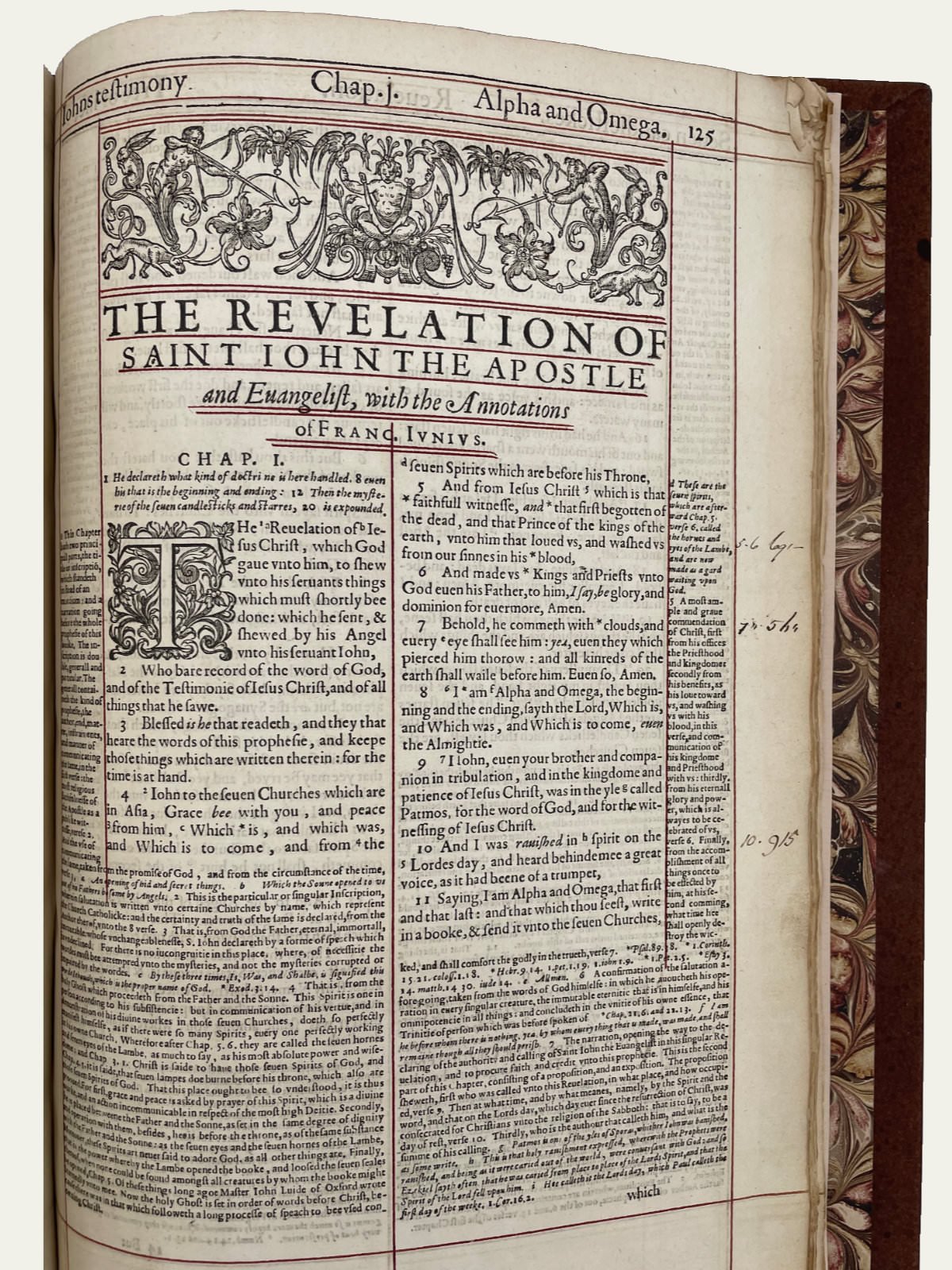

Tomson’s Revision and Junius’ Commentary

Junius’ commentary takes up almost as much space as the text itself

In 1576 another small octavo was printed in England with an entirely new set of marginal notes in the New Testament. Laurence Tomson issued a new edition in which he incorporated notes from Beza’s latest edition of the Greek New Testament issued in 1565. Some small changes to the text considering Beza’s work were also incorporated. From 1576 onwards Geneva Bibles are either ‘Geneva’ or ‘Geneva-Tomson’. Beza’s short marginal notes were directly translated from the Greek and inserted in Roman font, but Tomson also added his own notes and commentary. The marginal notes to the book of Revelation in both versions of the Geneva New Testament were notably short.

In 1601 that all changed. The book of Revelation with Junius’ long commentary was initially bound after Tomson’s Revelation with very few notes. By the following year Junius’ notes replaced Tomson’s in every Geneva Bible printed thereafter. The notes are Christological in nature and quite lengthy, frequently containing more commentary than text. Junius’ elaborate work contains a handful of notes that are strictly anti-papal in nature, but overall, he focuses the reader on the story of God and His people, as well as the redemptive work of Christ and His church.

Printing of the Geneva Bible Banned in England

Despite a concerted effort by the Church of England to thwart the Geneva Bible, the people still preferred it. King James worked to promote his authorized version, intentionally free of notes that questioned his authority. Printing it in England was already difficult because of supply and demand issues. Other countries used recycled cotton rags to make their paper. The English predominantly wore wool resulting in an inadequate supply of raw materials to send to the English paper mills. Still, the demand for Geneva Bibles remained and paper was imported from France. Eventually King James decided to ban the printing altogether. The 1616 quarto was the final Breeches Bible printed on the island.

Printers in Holland recognized the economic opportunity and became the sole source for Geneva Bibles imported into England after 1616. Eventually, in the 1630s, Archbishop Laud banned their importation. Not to be deterred, the Dutch made spuriously dated 1599 title pages to make their Geneva Bibles appear legal.

A contemporary London bookseller, Michael Sparke, notes how much cheaper the imported Geneva Bibles were, and charged the King’s Printer with commercial exploitations of his monopoly. Claims from Laud include that the imported Geneva Bibles were both superior in quality and more affordable, and the ban on importation was necessary in order to protect English printing houses.

The admiration and devotion towards the Geneva Bible and its notes did not subside overnight. Once the authorized version was printed in 1611, a Bible without notes altogether, King James made a concerted effort to promote his version over and against the Bible with notes that questioned his authority. The king made the decision to ban the printing of the Geneva Bible and a 1616 quarto would be the final Breeches Bible printed on the island.

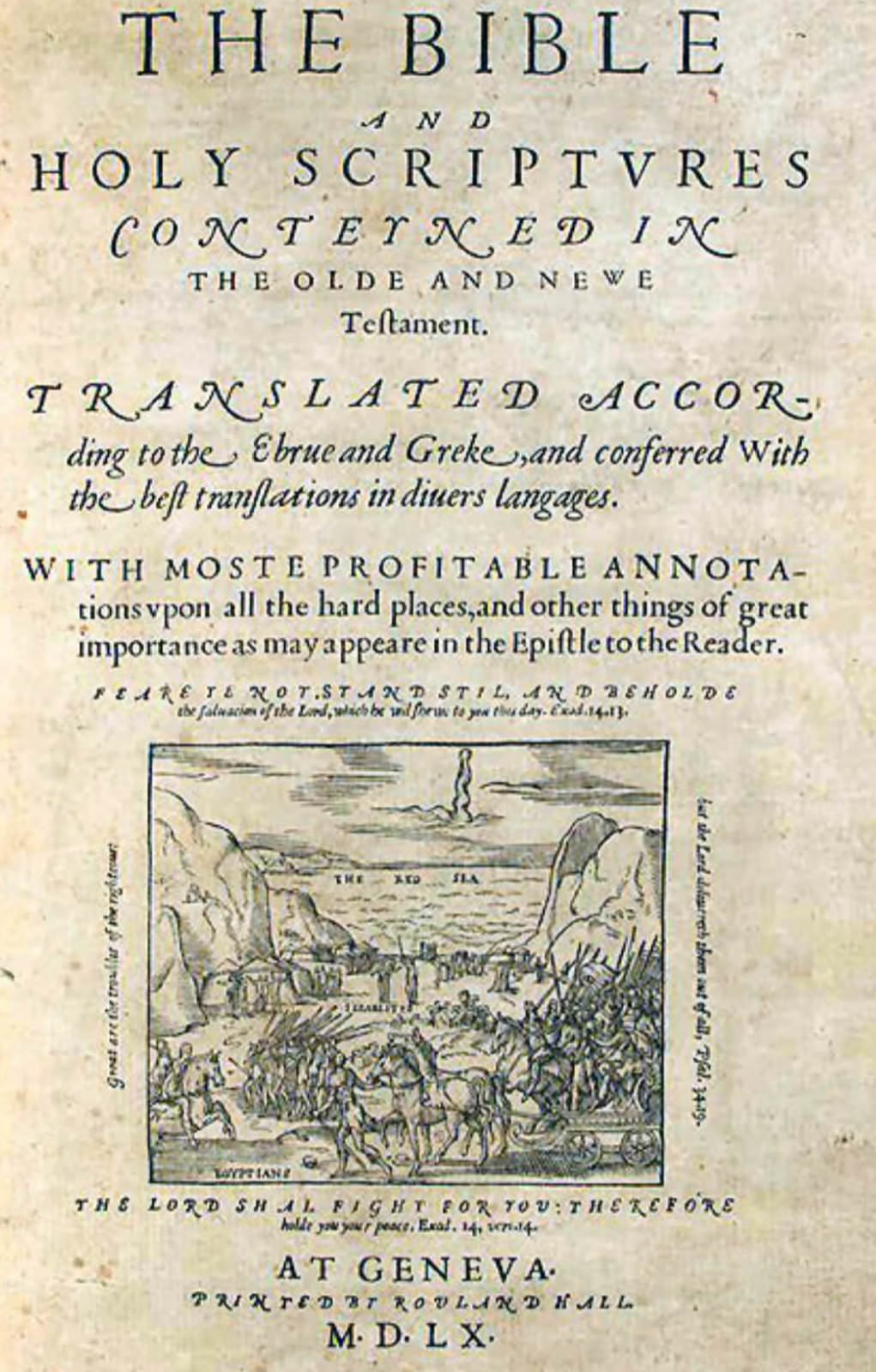

Geneva Bible Title Pages

In stark contrast to the folio Great Bible, Bishops’ Bible, and King James Bible, the Geneva Bible title page does not make strong political statements regarding government authority. Instead, it invites the reader into the text. The focus of the first quarto title page is entirely on the Scriptures and their promise. “Fear not, stand still, and beholde the salvacion of the Lord, which he will shewe to you this day. The Lord shal fight for you: therefore hold you your peace” (Exodus 14:13,14). The woodcut illustration is that of God parting the Red Sea and delivering His people from bondage toward the promised land. It is this freedom from oppression and supression that the English exiles longed for.

The 1562 first small folio edition brings the reader in by displaying a candlestick with the theme of showcasing the light of Christ. “No man lighteth a candell, for to put it under a bushell, but upon the candlestick” (Matthew 5:12).

1599 Geneva Bibles - Pirated Printing

Demand for the Geneva Bible remained high for years after its printing in England was banned. Printers on the continent jumped at the economic opportunity by publishing them in Holland and selling them for profit to eager readers across the North Sea. Both economic and political factors contributed to the new ban, not only on its printing, but also on the importation of the Geneva Bible into England by archbishop Laud in the 1630s. Certainly the anti-monarchic notes played a factor, but cost was also a consideration. The cotton rag paper used in printing and compiling antiquarian books was far less expensive on the continent since cotton was readily available. There were paper mills in England by the late 16th century, but those mills failed to prudence printing-quality paper. High quality paper was produced using cotton, whereas the English preferred to wear wool. Many Geneva Bibles were printed in Holland and imported with spuriously dated 1599 title pages in order to appear legal.

A contemporary London bookseller, Michael Sparke, notes how much cheaper the imported Geneva Bibles were, and charged the King’s Printer with commercial exploitation of his monopoly. Claims from Laud include that the imported Geneva Bibles were both superior in quality and more affordable, and the ban on importation was necessary in order to protect English printing houses.

1599 Geneva Bibles

The Geneva quartos printed in the 1630s were spuriously dated 1599

The Legacy of the Geneva Bible

Out of the eight printed English Bible versions that culminated in the King James Version, the Geneva Bible was by far the most popular. Both its convenient size and its beloved notes spurred on personal study of the Scriptures and increased literacy rates throughout England. It was a version crafted by a small committee of scholars in exile, hopeful that their work would ignite a passion for the reading and study of the Bible for the common man. There is renewed interest and resurgence in the Geneva Bible today - acquire your Geneva Bible and cherish this Reformation treasure!

References for further reading

Daniell, David. The Bible in English: Its History and Influence. Yale University Press, 2005.

Dore, J. R. Old Bibles: Or an Account of the Early Versions of the English Bible. Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1888.

Eason, Charles. The Genevan Bible: Notes on Its Production and Distribution. Eason & Son, 1937.

Hamel, Christopher De. The Book: A History of the Bible. Phaidon, 2001.

Herbert, A.S. Historical Catalogue of Printed Editions of the English Bible, 1525-1961. London and New York, 1968.

Norton, David. A History of the Bible as Literature. Cambridge University Press, 2000. (pp. 89-95).

Pearson, David. English Bookbinding Styles, 1450-1800: A Handbook. Oak Knoll Press, 2014.

Pocock, Nicholas. "Some Notices of the Genevan Bible." Bibliographer, Dec. 1881-Nov. 1884; Jan 1883. (pp. 28-31).

Pope, Hugh. English Versions of the Bible. B. Herder Book Co., 1952.

Werner, Sarah. Studying Early Printed Books, 1450-1800: A Practical Guide. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2019.