English Bible History

he impact of the Bible on history is truly remarkable. It boasts more surviving manuscripts from antiquity than any other literary work. Not only was it the inaugural book to be printed, but with approximately 5 billion copies sold and distributed, it stands as the most widely circulated book in existence. Old Bibles vary widely, some adorned with elaborate illustrations of fine art, while others remain quite plain. The cost spectrum is equally diverse, ranging from very expensive editions to affordable or even free copies.

When the Bible was initially printed and disseminated, it played a pivotal role in fostering increased literacy across the Western world. In the 15th and 16th centuries, for many individuals, the Bible was not only their first book but also their only one. Throughout the centuries, the text has undergone numerous translations and rearrangements, making its impact felt across countless languages and cultural contexts.

This is what makes the Bible and its history so fascinating.

Wycliffe Bible:

An Early English Translation

For over a thousand years, the text of the Bible was primarily in Latin. John Wycliffe (c. 1330-1384) and his following of academics from Oxford translated the Bible into English from the Vulgate by around 1384. Often referred to as the Morningstar of the Reformation, Wycliffe was spurred on by theological concerns regarding the supremacy of the papacy.

All of his writings were eventually ordered to be burned, he was declared a heretic, and his corpse was exhumed and burned. Any produced English translation of the Bible without permission from ecclesiastical authority was thereafter forbidden.

Factors That Contributed to the Distribution of Bibles in English

The Printing Press

Prior to the printing of the Gutenberg Bible, copying a page of Bible text was a time consuming and labor-intensive process of crafting manuscripts by hand. Some short sections of writing and pictures could be reproduced by etching into blocks of wood in reverse and then inking and stamping these blocks onto sheets of paper. Each page would need to be carved into a new block of wood in mirror image. The technological advancement spearheaded by Gutenberg was the invention of the movable type. A composition of mass-produced letters could be mechanically assembled to form one page of text, and many copies could be printed onto paper. Once the desired number of copies was reached, these letters could then be removed and reassembled to form the next page of text. Using his invention, Gutenberg produced the first printed Bible in Latin in the city of Mainz, Germany around 1453-1455. It is believed that Gutenberg printed around 180 copies of his Bible, which were all elaborately illuminated by hand. Amazingly, 50 of these original copies have survived to present day. Some say Gutenberg made the greatest contribution to civilization in the second millennium. His printing press forever changed the way books and Bibles were produced and distributed, making the written word more accessible and economical than ever before.

The Dawn of Humanism

In Italy during the 15th century, the Renaissance and humanism brought renewed interest to the Latin and Greek manuscripts of the Bible. In applying textual criticism, Lorenzo Villa created a detailed verse by verse comparison of several Greek manuscripts with the Latin Vulgate produced by Jerome. The famous humanist Desiderius Erasmus (1469-1536) stumbled upon Villa’s work and began compiling a New Testament in Greek based upon old manuscripts. From 1511 to 1516, he worked on his Greek New Testament with an emphasis on comparing Jerome’s Latin translation to his Greek text. He claimed to be improving upon Jerome’s version by calling out inaccuracies or misleading emphases in the text. His stellar reputation as a scholar and person of great influence kept him from running into serious trouble with the establishment. Even so, Erasmus was treading upon dangerous ground. The Church had used the Vulgate for hundreds of years and calling its accuracy into question had significant implications. Doing so would compromise the integrity of the teaching of the Church fathers, inasmuch as they quoted the Vulgate, and raise concerns regarding the accuracy of the judgments of councils. Nevertheless, Erasmus proceeded with his work and published his New Testament in two-column format—Greek on one side and Latin on the other. Erasmus’s work bolstered attempts at future translations of the Bible into contemporary languages by providing a compilation of original Greek to draw from.

Theological Factors

Martin Luther (1483-1546) was an Augustinian monk who served as chair of theology at the University of Wittenberg. In 1517 Johann Tetzel was sent to Germany to sell indulgences in order to raise money to rebuild St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. An indulgence was essentially a fund-raising certificate. Anybody could donate money toward a specific cause, and if their donation was pious, they were granted not only a certificate, but forgiveness of sin (either their own, or that of a deceased relative). Pope Leo X granted permission to sell a special plenary indulgence which would remove the temporal punishment of sin. Tetzel overstated the Catholic stance of indulgences purchased on behalf of the dead. His slogan was, “when a coin in the coffer rings, a soul from purgatory springs.” Luther got wind of this and wrote a letter to his bishop (in the academic language of Latin) stating his concerns, including what would become known as the ninety-five theses. Luther claimed that God alone was able to grant forgiveness for sins, so those selling indulgences must be in error. The tone of his letter was inquisitive and concerned, rather than accusative. His friends translated his ninety-five theses into German and used the newly-invented printing press to circulate Luther’s ideas. Within a few weeks his theses were spread throughout Germany. By the following year, they had reached Italy, France, and England. Luther grew in fame and gave lectures on various New Testament books. In doing so, he began to refine his understanding of justification. Luther believed that God’s favor cannot be earned. Rather, he believed it is granted through undeserved kindness to those exercising faith. To Luther, spiritual truth did not rest in Scripture and tradition but in Scripture alone. Luther objected to the Church’s teaching that the Pope had the exclusive right to interpret Scripture. He committed to translate the Bible into everyday German. Though there were already as many as 18 editions of the Bible in German, they were translated from the Vulgate, and many of the phrases seemed dry and incomprehensible. Luther combined Erasmus’ Greek New Testament text with his gift for writing clearly and articulately. By 1522, he completed his German New Testament, and the Old Testament was done sometime during the 1530s.

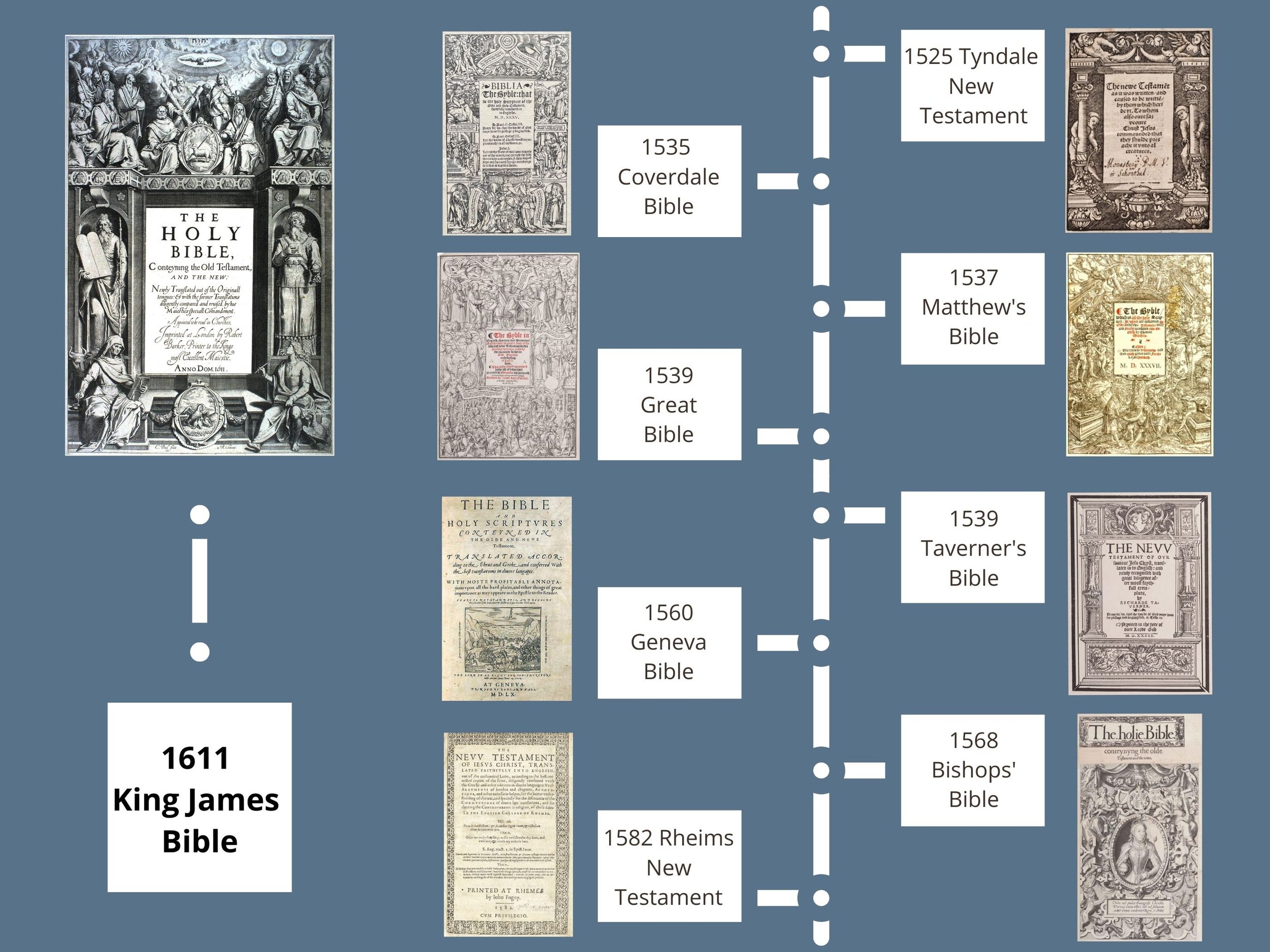

Printed English Versions Before the King James Bible

The King James Bible is the crowning jewel of English Bible translations,

but it stands upon the shoulders of giants.

Tyndale Bible:

A Scholar and a Martyr

William Tyndale (1494-1536) began to craft a new English translation of the Bible in 1524. Armed with Erasmus’ Greek New Testament and Luther’s German text, he completed his English translation of the New Testament in just one year. The printing shop was raided, forcing him to begin anew and he released a smaller version in 1526.

While working on his Old Testament translation, Tyndale was betrayed and arrested. He was convicted of heresy, strangled, and burned at the stake. His last words were: “Lord, open the king of England’s eyes.”

Within a year his prayers were answered. His colleague Miles Coverdale (1488-1568) completed the first English translation of the Bible in 1535.

John Rogers (1505-1555) worked on a translation that used Tyndale’s work, completing the Old Testament based upon the Hebrew text. This was released in 1537 under the pseudonym of Thomas Matthew. This Bible is known as the Matthew Bible.

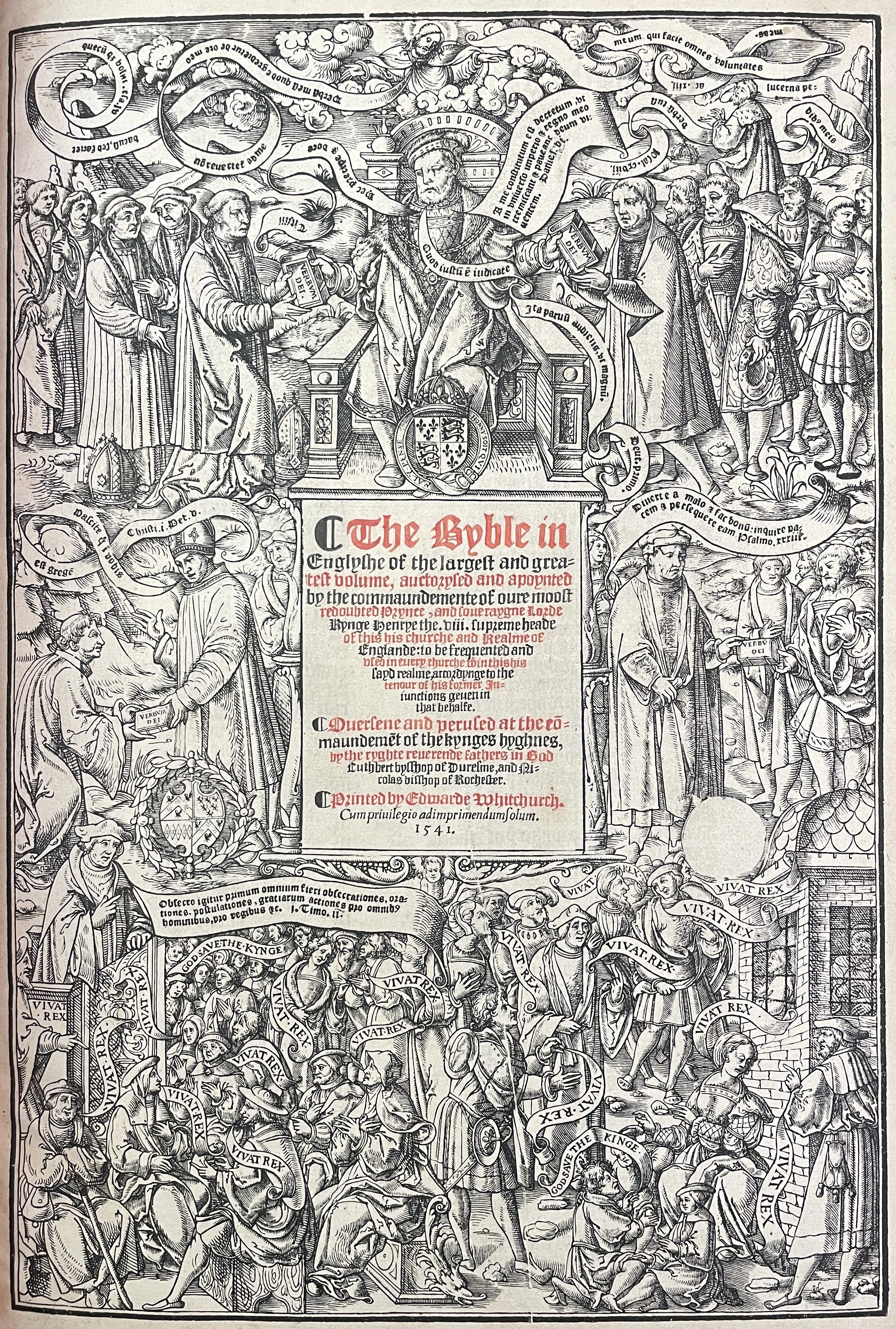

The Great Bible:

Placed in Every Church

Neither the Coverdale Bible or the Mathew Bible were widely accepted by the church, in part due to the notes and features that bishops in England found objectionable. The Archbishop of Canterbury commissioned Coverdale to create the Great Bible—the first English Bible authorized for daily use in churches. To complete the reversal from just a few years prior, by September 5, 1538, the king commanded that a copy of the English Bible be placed in every church in England. Hot off the press in 1539, the large folio Bible was often chained to the pulpit. Seven editions of the Great Bible were printed by 1541.

Geneva Bible: By the People, for the People

A devout Roman Catholic, Queen Mary, took the throne on July 19, 1553. ‘Bloody Mary’ sought to return England to Catholicism and was not afraid to persecute protestants for the cause. An exodus to the continent resulted in small settlement of exiles in Geneva, Switzerland.

William Wittingham and a group of fine scholars translated the text from the original Hebrew and Greek resulting in the Geneva Bible. Boasting wide margins, clear Roman font, and a smaller portable quarto size, the Geneva Bible was well received by the people.

The Geneva Bible was the first study Bible with detailed study notes provided in the margins. It is the Bible quoted by Shakespeare and the Bible that first crossed the Atlantic to the New World. You can find folio Geneva Bible leaves here.

A 1611 folio Geneva Bible in Roman font with the full page engraving of Adam and Eve in the Garden. Geneva Bibles can be bound with a Book of Common Prayer, engraved Genealogies, a Metrical Psalter, and Tables.

A spuriously dated 1599 quarto Geneva Bible with a full set of 33 illustrations and maps. Most copies dated 1599 were printed in the 1630s in Amsterdam and smuggled into England after the printing of the Geneva Bible was banned.

Bishops’ Bible:

A Response to Geneva

Many Anglican clergymen objected to the study notes in the Geneva Bible, particularly the promotion of elder-led church government. The accuracy of translation in the Geneva version also highlighted some errors in the Great Bible. In response, Matthew Parker sought to update the Great Bible. Scripture was divided into sections and distributed to Anglican Bishops. These Bishops were to independently review and update their section. Parker thereby compiled the Bishops’ Bible.

The result was a Bible beautiful in appearance but lacking in content. Containing over 120 elaborate woodblock illustrations, fresh title pages with portraits, and four maps, the Bishops’ Bible was a work of art. Unfortunately, the work was rushed, resulting in an inferior translation. You can find Bishops’ Bible leaves here.

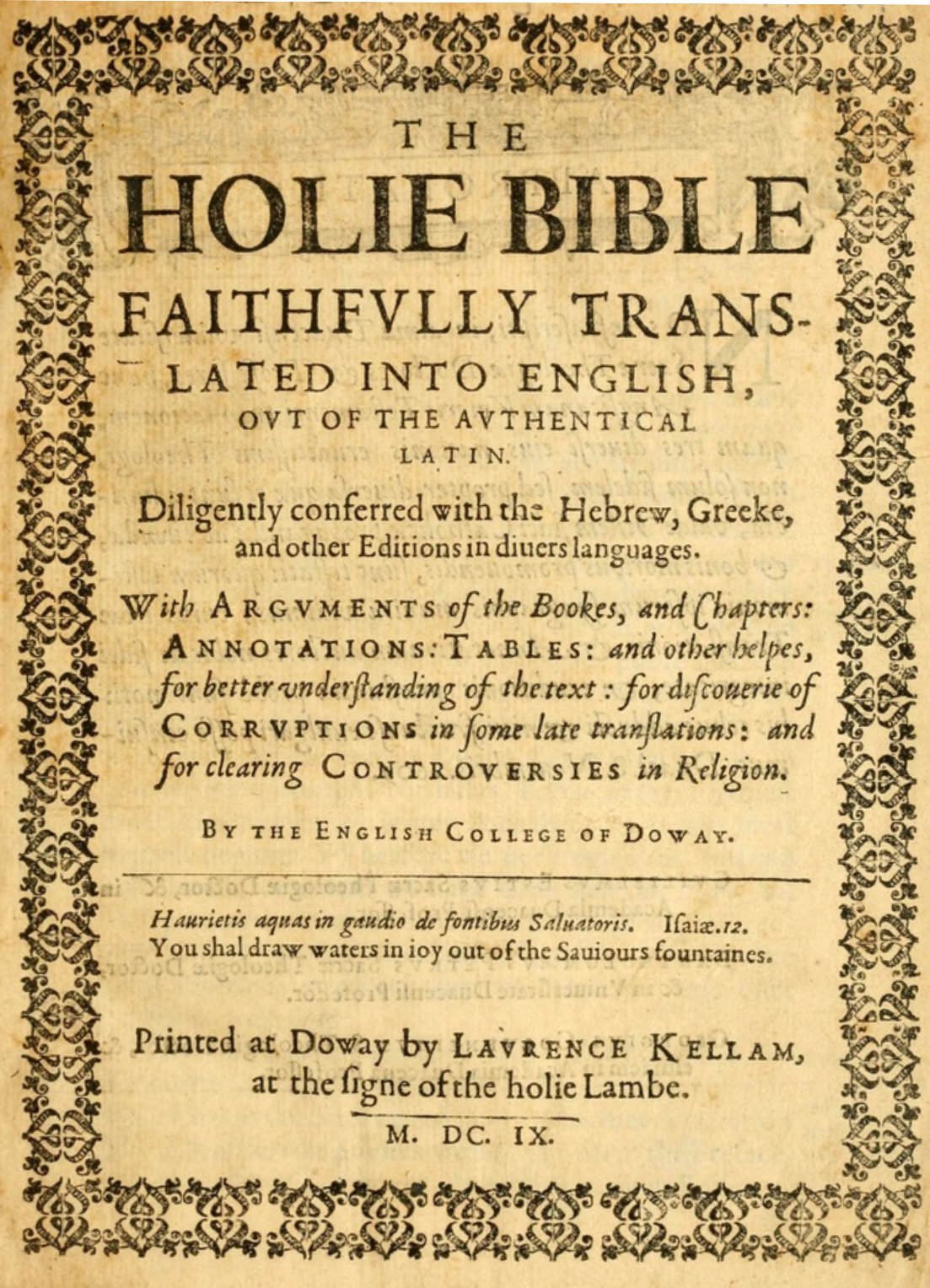

Douay-Rheims Bible:

A Translation from the Vulgate

Even though numerous English translations of the Bible were available by 1578, none were acceptable to Roman Catholics. A New Testament would be produced in order to enable Catholics to refute heretical ideas from neighbors who knew their Bible inside and out, and also to discourage adherents from reading any other English translation that might be readily available.

Gregory Martin began the work of translating the text of the Vulgate into English in 1578 at the Roman Catholic College at Rheims. The entire Catholic Bible would be completed by 1610 at Douay (hence the Douai-Rheims translation). At the Council of Trent a few decades prior, the Latin Vulgate was declared the only authentical Catholic text. The Bible was thus a translation of a translation. The Bible has wide margins and the notes are in clear type in the footer of the text.

King James Bible:

Most Important Book in English

Despite the popularity of the Geneva Bible among England’s laypeople, many Anglican clergy objected to it because of its study notes and departure from tradition. They wanted something more akin to the Bishop’s Bible in its intended use, size, and style, but with a more accurate translation.

King James I responded by calling for a new translation. University scholars worked in teams to translate directly from the Greek and Hebrew. Their work was reviewed by church leaders and ratified by the king himself. Though translation notes and cross references remained, all commentary was removed. The result was not only reliable, but beautifully written.

The King James Bible has been referred to as the most important book in English. Its impact on English language and culture is vast. While popularity for the King James Bible grew slowly, by the end of the 17th century the King James Translation was the dominant text. It would remain that way for centuries.

Vinegar Bible:

John Baskett’s Masterpiece

The Vinegar Bible is renowned for both its exquisite workmanship and its glaring errors. It was printed by John Baskett (1664-1742), a man of significant influence in the world of printing. Though he produced one of the most magnificent Bibles ever printed in England, he had a shady business reputation and was often criticized for his business dealings, carrying significant debts, and facing numerous legal challenges.

The presentation quality of the Vinegar Bible is truly stunning. With a richly decorated gilt spine and numerous engravings throughout, it served as an ideal status symbol for the elite. Unfortunately, once it made its way into the hands of the clergy, numerous errors and omissions in the text were discovered.

The Vinegar Bible gets its name from the most famous of the errors in the 1717 printing. The headline of Luke 20 reads, “the parable of the vinegar” (instead of vineyard).

The title page to the book of Matthew of the 1717 Vinegar Bible by John Baskett

A pulpit folio Vinegar Bible with richly decorated gilt to the spine

Macklin Bible: Most Impressive Bible Ever Printed

The largest and most impressive Bible printed—a multi-volume book (usually six or seven volumes) that weighs well over 100 pounds! Each volume is illustrated with multiple copper plate engravings after paintings by some of the foremost artists of the day. This amazing set was the work of Thomas Macklin (1752-1800), a British 18th-century print seller and picture dealer.

Among the 700 subscribers to the enormous production was the royal family. Macklin died on October 25, 1800, just five days after the last large engraving was finished for his Bible.

According to the Dictionary of National Biography, “The Macklin Bible endures as the most ambitious edition produced in Britain, often pirated but never rivaled.”

Above: Some of the hundreds of illustrations found throughout the Macklin Bible

The seven volumes of a complete Macklin Bible. Some collectors had additional illustrations bound in, thereby increasing the number of volumes.

Harper’s Bible:

A Remarkable Production

The engraver Joseph Adams (1803-1880) began the most innovative of all American Bibles. He convinced the Harper and Brothers publishers to take on ‘the most splendidly elegant edition of the Sacred Record ever issued.’ The finished product includes over 1600 historical engravings and in-line illustrations.

Adams is credited with having taken the first electrotype in America from a woodcut. Many illustrations in this Bible are done this way. Artists were engaged for more than six years in the preparation of the designs and engravings included in this Bible, at a cost of over $20,000, a small fortune in those days.

A page from the Harper Bible providing a sampling of the over 1600 illustrations throughout the text.

The Bible was initially issued in 54 magazine issues. Once all issues were released, subscribers could have them bound together into one volume. For an extra cost, the owner could have a picture of their church engraved on the cover.

Family Bibles:

A Library unto Itself

Family Bibles, the one-stop-shop for Bible reading and Bible study, increased in popularity throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. The family was considered a little church and the father was responsible for leading his family in Bible study and worship. Additional study aids were incorporated including an overview of denominations and notes to help explain the Scriptures. These Bibles had beautifully decorated covers, with gold gilt page edges, and metal closing clasps. Ornate family Bibles became so common that they could be purchased from a Sears catalog!

By the 1880s the large family Bible had become a library unto itself – weighing up to 18 pounds! In addition to the Scriptural text, these Bibles contain numerous illustrations by the famous Gustave Doré—some of which are color—as well as detailed maps. A chronological index, concise harmony of the gospels, and a Biblical Cyclopedia could be bound in as well. These family Bibles were available in Protestant and Roman Catholic versions. Bible salesmen were given the task of going door to door to advertise and secure the sale of a family Bible that could be tailored to meet the customer’s request.

Roman Catholic Family Bibles include text translated from the Latin Vulgate. The pages have gilt edges and are filled with elaborate illustrations. Numerous study aids such as dictionaries, commentaries, Catholic histories, and maps are present. Stations Of The Cross and The Life Of The Blessed Virgin Mary are sometimes included. A family records section is included to record family history.

Protestant Family Bibles have decorated covers with illustration of Bible scenes. The text is the King James Version with the Apocrypha included. The pages have gilt edges and metal closing claps. These Bibles contain many illustrations, dictionaries, overview of denominations and other study aids. A family records section is included to record family history.

References for further reading

Daniell, David. The Bible in English: Its History and Influence. Yale University Press, 2005.

Hamel, Christopher De. The Book: A History of the Bible. Phaidon, 2001.

Herbert, A.S. Historical Catalogue of Printed Editions of the English Bible, 1525-1961. London and New York, 1968.

Norton, David. A Textual History Of The King James Bible. Cambridge, 2005.